How does a boat float?

At first glance, it might seem strange that a heavy boat made of metal or fiberglass can float on water while a small rock sinks instantly. The reason lies in the principles of physics — particularly buoyancy, density, and displacement. Understanding how a boat floats helps boaters appreciate the science that keeps their vessels stable and safe on the water.

The Principle of Buoyancy

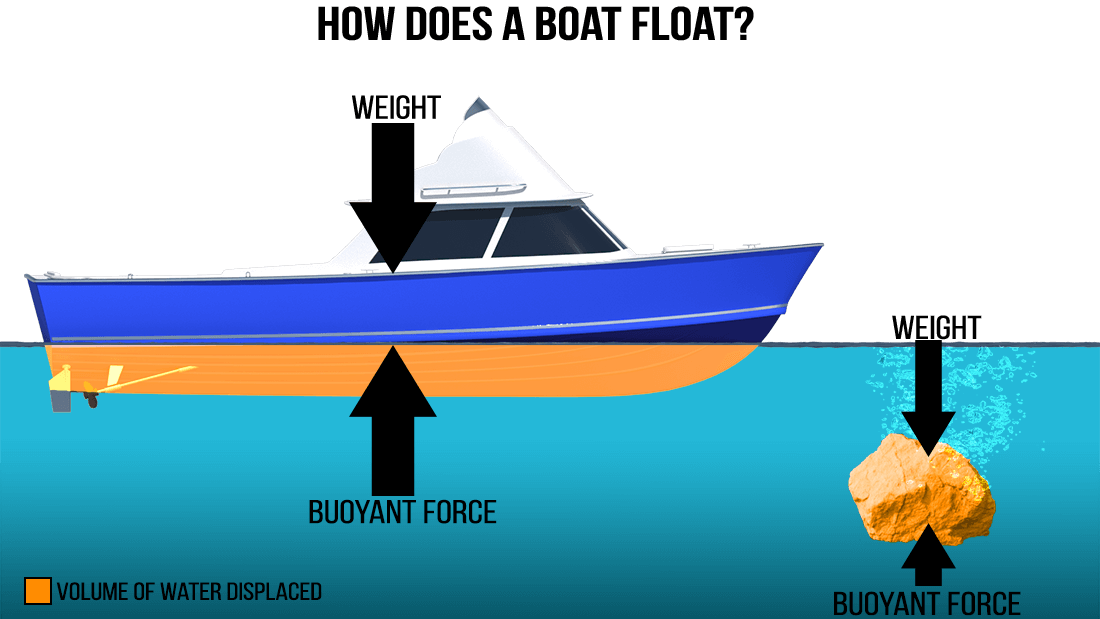

The main reason a boat floats is because of buoyancy, a force that acts upward on an object placed in a fluid, such as water. This principle was first described by the ancient Greek scientist Archimedes. His discovery, known as Archimedes’ Principle, states that:

An object placed in a fluid experiences an upward force equal to the weight of the fluid it displaces.

In simpler terms, when a boat is placed in water, it pushes some of that water aside (displaces it). The water then pushes back with an equal force in the opposite direction. If the upward buoyant force is equal to or greater than the weight of the boat, the boat floats.

Density and Displacement

A key factor that determines whether something floats or sinks is density, which is the measure of how much mass is packed into a given volume. Water has a specific density (1 gram per cubic centimeter in freshwater). If an object’s average density is less than that of water, it will float.

Boats may be made from dense materials like steel, aluminum, or fiberglass, but they are designed with hollow hulls filled mostly with air. This gives the entire boat a much lower average density than solid metal or wood. Because of that lower density, the total weight of the boat and everything in it is less than the weight of the water displaced by its hull — allowing it to float.

For example, when a large ship sits in water, the shape of its hull causes it to displace a huge volume of water. The water that’s displaced weighs as much as or more than the ship itself. This balance of forces keeps the vessel afloat.

The Role of Hull Shape

A boat’s hull design is also crucial to its ability to float and remain stable. The hull’s curved or V-shaped bottom spreads the boat’s weight over a larger area, displacing more water. This helps increase buoyant force and improves stability, even when carrying heavy loads.

Flat-bottom boats, such as small fishing boats, displace water evenly and float easily in calm, shallow areas. Deep-V hulls, found on speedboats and offshore vessels, are designed to cut through waves while still providing buoyancy and stability at high speeds. Sailboats and larger ships have rounded or keel-shaped hulls to balance weight and prevent capsizing in rough seas.

Equilibrium and Stability

Floating isn’t just about staying above the surface — it’s also about staying upright. A boat must maintain stability, which depends on the relationship between its center of gravity (the point where its weight is concentrated) and its center of buoyancy (the point where the buoyant force acts).

If the boat tilts to one side, the shape of the submerged part of the hull changes, moving the center of buoyancy to counterbalance the shift. When properly designed, the buoyant force pushes upward through the boat’s center of gravity, returning it to an upright position. If a boat’s weight is poorly distributed — for example, if passengers all stand on one side — the center of gravity can move too far from the center of buoyancy, and the boat may capsize.

Why Boats Sink

A boat will float as long as the weight of the water it displaces equals or exceeds the weight of the boat. However, if water enters the hull (due to leaks, overloading, or waves), the boat’s weight increases while the displaced volume stays the same. Once the boat’s overall weight becomes greater than the buoyant force, it loses flotation and begins to sink.

That’s why drain plugs, bilge pumps, and proper loading practices are essential. They prevent water from accumulating and ensure the vessel maintains its buoyancy.