Limits of the operator, the boat and the environment

Knowing the limits of the operator, the boat, and the environment

It is important to be aware of our own capacities when we go on the water. The operator must rely on his experience and his acquired skills to determine if he is qualified to navigate the body of water safely. As well, the operator must ensure that he is familiar with the craft’s limitations and handling capabilities. Remember that each boat is different and reacts differently on the water. A larger boat needs a longer braking distance.

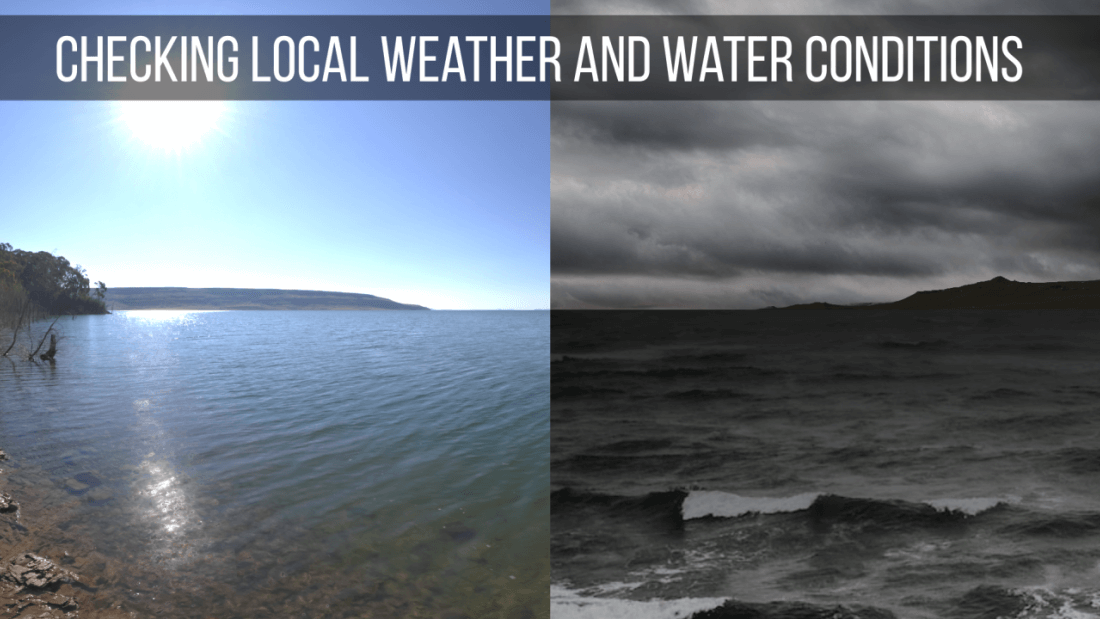

Identifying weather and water condition emergencies

Weather and water conditions play a big role in your safety on the water. Before heading out, make sure you get the latest forecast for your area and that you understand what it means. You should also be aware of local factors (like topography) which may cause weather conditions to differ from the forecast. People who know the area are the best source for this kind of information. Because summer storms can arise quickly and unexpectedly, you need to stay vigilant and monitor the sudden changes in the weather. If the sky begins to darken and the weather conditions change, you need to take shelter in a safe area. Before heading out, checking navigationnal references such as the charts and tides tables published and updated by the Canadian Hydrographic Service (CHS), or Sailing Directions or some Cruising Guides will help you to identify places to take shelter in event of foul weather.

Local hazards

Rapids are considered a local water hazard because they represent a permanent hazard at a determined place. They have strong turbulent currents which makes the craft less maneuverable. Rapids are usually shallow and are scattered about the surface of the water. They conceal rocks just below the surface. Rapids, therefore, endanger the pleasure craft and the crew.

The presence of overhead cables above the navigable waters represents a local water hazard, since they are permanently installed. If you are navigating in a sailboat, it is important that you properly evaluate the space between the top of the mast and the overhead cables, because the danger of electrocution is real. Many pleasure craft operators have had their nautical trip end in a dramatic way when their mast came into contact with overhead cables.

Underwater cables, (laid on the seabed) are also a grave danger. When you drop anchor, it can touch the underwater cable, thus provoking electrocution. You could also capsize the pleasure craft while trying to haul in an anchor which is caught on the cables. There are usually billboards on the water signaling the presence of underwater cables.

In restricted visibility such as fog or night navigation, the regulations require that the operator adopt a speed according to the conditions.

Sudden winds provoked by specific types of shorelines that surround the body of water may also represent local water hazards. Winds can, without warning, rapidly change speed and direction, thus compromising the safety of your pleasure craft. In shallow water, and when the wind intensifies, the waves can become very large and will break; thus, making it very dangerous to navigate.

Tides and currents add to the complexity of navigation. When the tide is in the opposite direction of the wind, you will face the ripples of the waves and this may capsize a pleasure craft, even if the wind is light. In certain places waves can become big very rapidly, especially in waters such as the Great Lakes or the St. Lawrence River where the waters are large enough to allow big waves to form. You must avoid areas where there are rapids or strong currents in order to not capsize. It is also important to know the high and low tides when you anchor, in order not to have the unpleasant surprise of ending up on dry land at low tide.

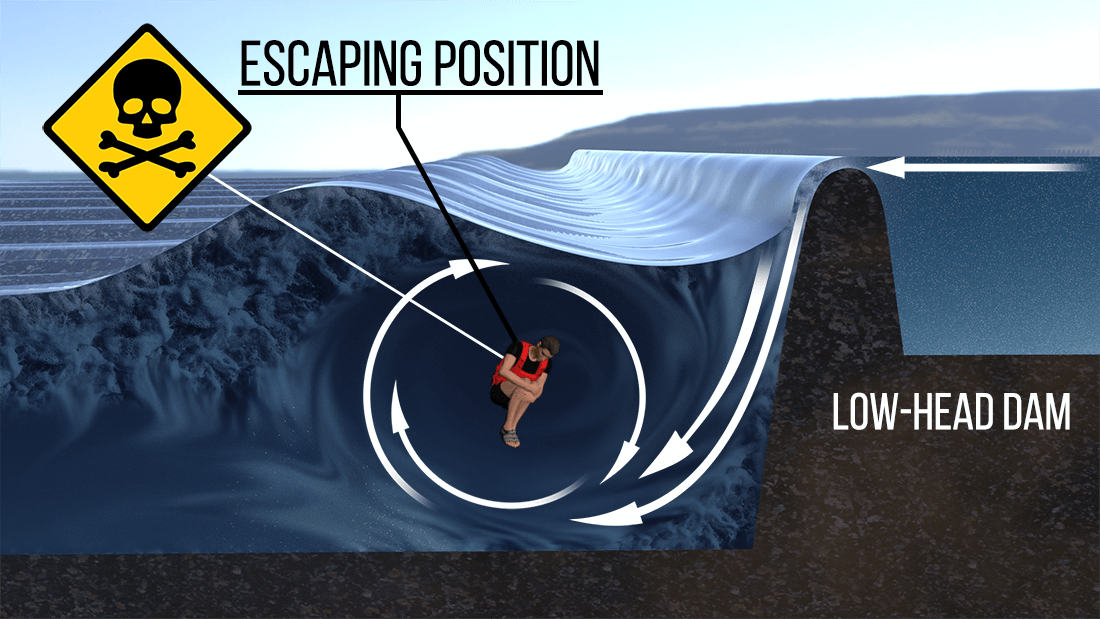

Getting too close to hydro electric dams is always dangerous. A spot that seems calm and safe one moment can turn into a dangerous surge of rising and fast-flowing water – quickly and often without any warning.